About

Hey! I'm LaSean. CAGR Investments (CAGR) is a micro-private equity firm I run. We are a small, distributed, twelve-person team. I'm in Seattle, WA. The firm allocates permanent capital to buy, own and operate profitable businesses that we hold with no intention of selling. Our focus areas include digital goods, membership sites, and SaaS. We do not buy Amazon FBA, e-commerce businesses, or businesses selling physical products. We are interested in companies with at least $500K in annual Seller's Discretionary Earnings (SDE), which are closely held, and privately owned. We buy 100% of the equity in the business. We seek entrepreneurs selling healthy companies transitioning to another idea or life stage. Valuations are reasonable and fairly priced based on net profit. We will save an entrepreneur's time and typically return a term sheet within three business days. If CAGR isn't a good fit, we will try to recommend other paths. There are plenty of other firms acquiring this class of company. You have options. Entrepreneurs interested in exiting their business should contact our deal desk at grow@cagr.com. In addition to digital companies, we occasionally purchase and incubate local businesses where our expertise can make both a positive cultural and financial impact. Finally, we incubate and operate new digital businesses when that path is more beneficial than purchasing an existing company. Unlike the traditional venture studio model, we start companies that we plan to hold for years.

The purpose of publicly publishing content on why the firm exists is fourfold. First, it helps provide clear direction for the business. I perform better when I write things down and share them in public. Second, it provides future leaders of our portfolio companies a peek into our why, what and how. Third, I meet young adults who ask what I do and it's helpful to be able to point them to something provides ideas on career paths they may have not considered. Finally, sharing my why in public can be a useful reference to other founders as an example of strategic clarity. A huge part of winning as an entrepreneur or investor is figuring out when to say no. There are many ways to build and sustain a financially successful business. This is my approach as a reference in case you are looking for examples to refine yours.

Options (Not That Kind)

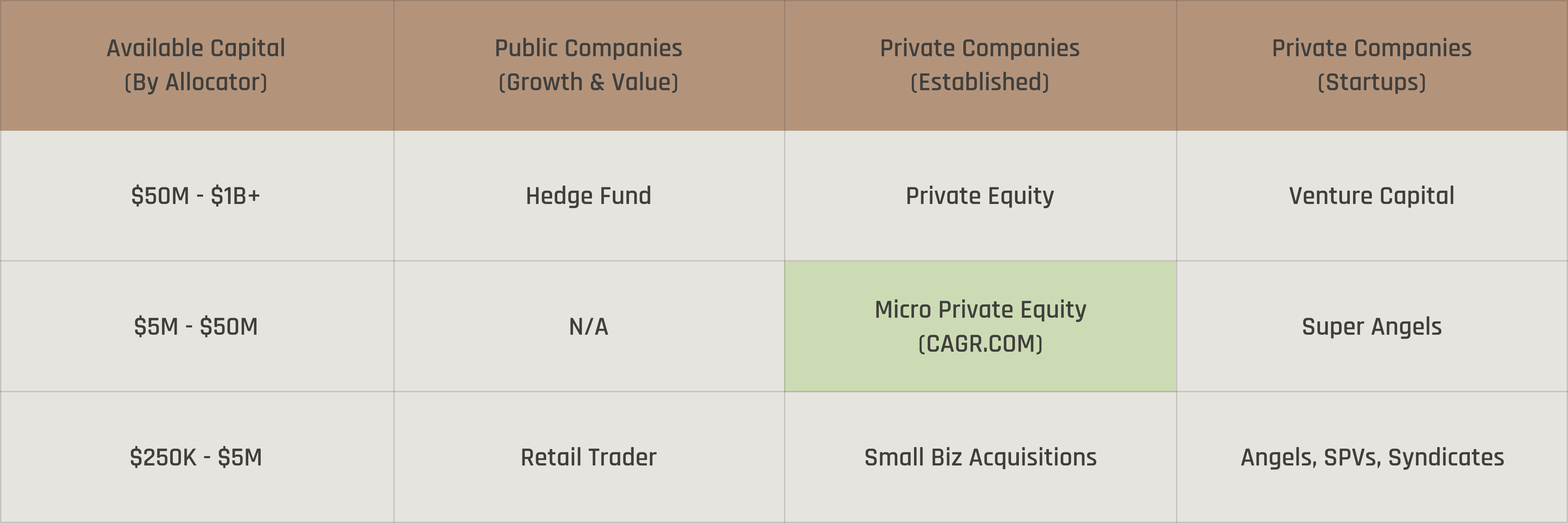

The impetus for founding CAGR was to create a small family office that could turn my ideas into cash-flowing assets. I started with real estate and quickly found it moved too slowly to keep my brain engaged. Sell-side opportunities also don't interest me, so I focused on the buy side. Angel investing was my next stop. Angel investing is currently broken and waiting 7-10 years to see if my $50K investment will turn into $1M isn't rewarding. Plus early stage valuations are still too high (even in the current market downturn). So even with a portfolio approach where you allocate $2M to angel investments (example: 20 investments at $50K each and another $1M for pro rata follow on) the actual returns aren't that great. I considered starting a hedge fund, private equity, or venture capital firm. Hedge funds focus on liquid assets — often public equities (i.e., the stock market). Playing in the highly manipulated and volatile public markets wasn't interesting, so I crossed that off my list. Crypto hedge funds play in a space that is even more blatantly manipulated. That's like the old saying — don't spend time in a casino unless you own the casino. Private equity (PE) firms typically buy distressed and established companies using debt. They improve the financial position of the companies they buy and attempt to sell them for a profit in 5-10 years. The traditional PE model of flipping companies at the expense of the humans inside those companies isn't attractive. This isn't always the case, but the work is more about the spreadsheet than the people. Venture capital (VC) firms typically invest in early-stage and growth companies. VC investments are highly illiquid, and it is not uncommon for a VC fund to take over a decade to return capital.

In all these options, the general partners (GPs) that run a hedge fund, PE, or VC firm typically raise money from limited partners (LPs) and invest the LPs' money. GPs get paid with a fee structure called "2 and 20". These numbers are negotiable, and a “1.5 and 15” fee structure is not uncommon. The general math works like this. The investment firm charges LPs (sometimes referred to as clients) a 2% management fee and a 20% performance fee. The 2% management fee is an annual fee applied to the LPs' total assets under management (AUM). The 2% management fee can be paid on a straight-line basis over the fund's life or be paid on a "step-down" basis triggered by certain events. The 20% is a performance fee (sometimes called an incentive fee or "carry"). When calculating profits for an investment firm, the LPs get their invested capital back first — plus some preferred return (also called a "hurdle rate"). Once the hurdle rate is met, the GPs get their carry. The sequence of these cashflows is referred to as the equity investment waterfall. A GP catch-up is a negotiable inclusion used to "catch up" GPs to their target carry after the LPs have reached their hurdle rate. Here's an example equity investment waterfall. A firm raises a $100M investment fund. The GPs get $2M each year to pay themselves and operate the fund. There will be good and bad returns in the fund. Let's say the fund returns $180M after management fees. With a 10% hurdle rate, the LPs will get $100M of their initial capital, $18M in preferred returns, and $49.6M of the balance (80% of the remaining return). That leaves the LP with a total return of $167.6M. The GPs would make $12.4M (their carry) plus ~$14M in management fees if the fund ran for seven years. That's $26.4M to operate the firm and pay the GPs. A small firm with three GPs and 80% gross margins will leave each GP with $1.26M per year. I'm simplifying the math here for the sake of the example, but the main takeaway is that I don't think making $1.26M per year is worth the trouble. And that's assuming you could even raise a $100M fund your first time out. There are more challenges here for PE and especially VC. First, it takes many years to figure if you're any good at the job. VCs like to talk about the value of their fund using a metric called TVPI (Total Value to Paid In Capital). It's the sum of the fund's realized and unrealized holdings divided by the capital called by the fund (i.e., the money paid in by the LPs). These multiples can make it look like venture capital is the best growth asset class to place your money as an LP. However, TVPI is a hustle. IRR (Internal Rate of Return) is also a poor way to value a fund, although it can still be useful for directional analysis. Both IRR and TVPI are irrational and easily gamed metrics. For example, a VC could invest in an existing portfolio company at a valuation they know is inflated. As a result, TPVI goes up even though nothing has changed with the portfolio company's cash flow or fundamentals. You should be getting Ponzi vibes at this stage. A better way to measure the performance of a GP is to look at their fund's DPI (Distributions to Paid-in-Capital). This is how much money a VC fund has sent back to LPs divided by the amount of money the LP has paid into the fund. DPI isn't popular as an anchor metric for GPs or LPs because it takes years to do the math. But here's the kicker. Most VC funds only return ~2x in DPI over a fund's total 7-10 year lifecycle. This isn't bad for an institutional investor. But for individual LPs, this is not an asset class you invest in to provide outsized returns. And again, neither the GP nor LP will know if a specific GP is good — for years. Second, you need a lot of AUM to make real money as a GP. That's how many GPs actually get rich — the fees. A puny $100M fund ain't gonna cut it. The resulting real job for many GPs is raising money from LPs. Boring. Megafund PE and VC firms take advantage of these dynamics. They have years of operating history and so much AUM that they don't need to make high returns. Why? Once a firm's AUM gets big enough, the GPs raise money from institutional investors (e.g., insurance companies, pension funds, and university endowments). These institutional investors prioritize predictably over the risk of potentially higher returns. Side note, the mega funds have seen large paper IRR gains over the last few years, where short-term pandemic fuel growth and access to cheap capital have distorted the true value of the companies in their portfolio. So even the mega funds may not do so well in this current cycle. These collective challenges add up to headaches for new fund GPs.

Here's a finer point. Blackstone (BX) is the largest and one of the most successful PE firms in the world. In 2022 their stock price slid 37%. By comparison, the S&P 500 slid 16%. Bill Gurley and Benchmark Capital (which takes a 30% carry) is arguably the most successful VC firm over the past twenty years. Benchmark's debut fund returned LP capital 92 times and included the $6.7M eBay investment — potentially the best VC investment of all time. Benchmark has had many hits (Dropbox, eBay, Instagram, Twitter, Uber, Zendesk). But that was their exception, not the rule. Benchmark Capital is only in the 20% IRR range and ~2x DPI over the last few years (when you exclude paper gains). It's not apples to apples, but the S&P 500 generates a net IRR of about 12%. On average, PE and VC firms don't return astronomically higher returns than just buying an index fund. These numbers get even worse for PE and VC when calculating their risk-adjusted return (the Sharpe ratio). Inflation and other macro drivers further impact these numbers, but the takeaway for me is this. I don't have the data to believe I would be a better capital allocator than Blackstone or Benchmark Capital. So the only way for me to make decent money from investing other people's money is by running a firm with a high AUM. Pass. That's about flying around to offices and raising money instead of helping companies make things. Boring (for me). As a tech exec, my market value is $1M-$2M per year in total comp. This compensation is taxed much higher than a GP would make since their carry is taxed as long-term capital gains and not earned income. Still, the math shows that a moderately successful GP at a VC firm makes about what a run-of-the-mill tech executive makes. You take on a fiduciary duty when taking an LP's money. So you can't easily quit your job as a GP if you want to do something new. I'd rather work in big tech than be a GP. However, big tech has its own issues. And as an organization leader, I was not getting enough hands-on time to actually make things. For some execs moving away from the hands-on making of things is the goal. Not me. In evaluating the options above, I found the risk (β) for starting a hedge fund and VC was too high for me as a GP. The work in big tech was not as fun as it used to be. And PE's focus on distressed and turnaround companies wasn't the type of work I wanted to do. So what should I have done? Stayed in big tech? Started a fund that would amass $300M+ in AUM? Return to founder status and raise money from these VC GPs to fund a high-growth startup? Fat FIRE? I ended up back on the private equity track — specifically micro private equity using permanent capital. Here's why.

Micro-Private Equity & Permanent Capital

I discovered thousands of healthy existing small businesses owned by individuals looking to retire or transition to their next chapter in life. These are profitable standalone businesses generating less than $10M. A subset of these businesses have enough free cash flow to support hiring a CEO to run the company. These are businesses that never need to raise additional capital. There is limited guessing on whether these businesses can be successful. It's simply an audit of the financials and talent. I'm in the US, and this business class is also eligible for SBA loans. That means these businesses can be purchased for 0%-20% out of pocket when paired with owner financing. As a result, a business that generates $4M in revenue and $1M in SDE (a small-business metric similar to EBITDA) on a 3x multiple can be purchased for $600K out of pocket ($3M sales price; 20% of that is $600K). So after buying just two of these companies, you could generate the same income as a GP at a VC firm — with much less risk. Over time the SBA loan becomes a headache, and buying the businesses without leverage is the more practical path. I estimate a single GP with a small staff could acquire and hold 20-30 of these companies. Another compelling attribute is that the SBA loan option is debt. So once serviced, the GP would own 100% of the cap table. CEOs and employees can be awarded phantom stock so that they are incentivized to grow the company. This model gets even more interesting when you apply it to content and software companies. There are startups that have raised tens of millions of dollars in capital that will never turn a profit with their current burn rate and management structure. Before the recent economic downturn, founders of flailing companies would turn to a big tech or media company and sell themselves on the cheap. This would provide the investors and possibly founders with some cash — even if the acquisition didn't recoup the total dollars the startup had raised to date. The acquiring company would get talent. This was especially valuable when software engineers were extremely scarce. The world is different today. With fewer acquirers in the market, founders are often faced with the outcome of just shutting down their startup and writing the investment down to zero. For better or worse, it's a great time to be on the buy side of the market. In the last downturn, there were startups that had raised over $100M, selling for $5M. These types of deals are back. And that's where it gets exciting for me. The purchase price of these businesses are so small (businesses typically valued at less than $5M), I don't need LPs at all. I have a few million dollars of my own capital to allocate, and micro-private equity (micro-PE) provides a path for me to build a portfolio of companies without needing to raise outside funds. No permission. I plan to raise LP capital in the future. But that will be once I have a demonstrable track record and more leverage in the negotiation. What's the catch for micro-private equity? This path is much more work. More specifically, you have to work on three things. The determination to hunt for amazing deals in unexpected places. The discipline to "productize process" while staying out of the CEO's business. The drive to hire and develop a family of high-performing CEOs. This combo of deals, process, and talent, paired with my next insight — content-led sales — creates an unfair advantage for those willing to do the work. Many of these businesses for sale have poorly run marketing and sales functions. Their business is doing less revenue than possible due to poorly run sales and marketing functions. One way to solve this is to hire the best salespeople. A sales team is required for B2B businesses to grow to tens of millions in annual revenue. However, smaller companies don't need great salespeople. They can generate millions in annual revenue with junior sales talent paired with engaging organic content. This is content created for a company's blog, podcast, or social media accounts to constantly fill the company's sales funnel. This approach works without spending a dime on advertising. If you care about prestige and social validation, micro-PE probably isn't the path for you. If you are optimizing for passive income and are tired of professionally grinding it out, micro-PE probably isn't the path for you. However, if some combo of finance, media, and software is part of your talent stack, this is one of the most predictable paths to becoming a deca- or centi-millionaire will retaining the most control over your personal freedom.

Focus

This collective set of insights above provide the focus for my portfolio of companies. Here are a few of my rules. Find exceptional businesses for sale or incubate new ones. Obsess over process. Hire and develop great talent. Go to market with organic content marketing at the core. Don't spend money on advertising or trade shows. Keep sales teams small. Do all of this with permanent capital. Structure these businesses without the expectation that they ever have to be sold. There is a down side to this approach — the business will not grow as fast. But that's okay when there is no LP to pay back and the hero success metric is Free Cash Flow. I have another more personal rule for my business — no sales-focused business travel. I don't enjoy the dance anymore — so I don't do it. I'll get on a plane to shoot content. However, I won't get on a plane to chase a sale. If a deal can't get done remotely, I'm willing to lose that money.

Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) is a business and investing term for the geometric progression ratio that provides a constant rate of return over a given time. Despite the term's negative connotation after Wall Street bros popularized it, I love this concept. I use this formula as a compass to guide the firm's growth. Not only for how I make money but how I empower others to do the same. It's all about compounding growth. This concept applies to personal growth, relationships and wealth. Contact me at grow@cagr.com if you're interested in working at a CAGR portfolio company and growing together. There are plenty of ways to make money. Unfortunately, many corporations, educators, folks in the media, and institutional investors will mislead you into believing there is a "best way" to make money. That's not true. What's most important is that you have the self-awareness to follow the path optimized for what YOU want and what YOU are willing to spend to get it. CAGR Investments is a place that celebrates people that leverage their unique talent stack and maintain their own professional charter. Mine is simple: Know thyself. Make things. Stay free.

Move Without Permission

Naval Ravikant argues that there are four types of leverage: capital, code, media, and people. In an excerpt from Eric Jorgenson's compilation of Naval's writings, there are distinctions between these four types of leverage. Capital and people are proven forms. However, they both require permission. Someone has to give you the capital. Someone has to choose to work for you. On the other hand, you can create content and software companies that work for you while you sleep. It's not (yet) practical to repeatedly build a meaningful cash flow stream (e.g., $10MM in annual EBITDA) with zero capital and zero people. However, it is possible to reach those numbers with a relatively meager investment for businesses that combine content and software. By low investment, I mean less than $500K in lifetime funding for a company. And small teams that only get up to 24 people (many who do not need to hold employee status). These types of businesses will rarely become startup unicorns. That's not the goal. However, a portfolio of these companies can generate $80MM to $100MM in EBITDA per year. For a founder, that's a more valuable and resilient cash flow stream than you'd personally realize operating a single unicorn (i.e., a startup valued at over $1B).

Over the years, I've met fascinating people who have made their wealth in various ways. My takeaway is that there's no single path to building wealth. But you should choose a path that works for your personal goals and values. For example, building wealth through real estate isn't for me. It moves too slowly to keep my brain engaged. Boring. Plus, you should invest in areas where you have spent years learning. My background has been at the intersection of media and software. That's where I continue to focus. Further, I anchor on businesses that lean into truly permissionless audience building. This means Discord communities, newsletter businesses, social media, and YouTube channels. These are more interesting to me than creating content for a permission-based company like Disney or Netflix. The permission-based partners might boost your ego, but dealing with them is rarely worth the headache if your goal is to make money. Software is broad and is also an area where it helps me to refine my focus. I'm most excited about API services and SaaS products centered on process automation. Many SaaS products are still just "forms over data" — humans typing into web forms and commenting on data. That is paired with the per-user pricing model that drives the bulk of today's B2B SaaS. RPA products are building momentum and extending that paradigm. However, there's an opportunity to further reduce or even remove human-in-the-loop interaction in SaaS products. There will be an entire category of products where you hire unattended software to operate a complete job. I'm bullish on categories such as Generative AI that will reshape or eliminate the need for companies such as Fiverr. This unlocks a new class of products where automation-centric software companies can sell Leverage-as-a-Service to other companies. More code and fewer humans. The moral implications of this path are worth more discussion. However, the transition to code-first rather than human-first staffing is an inevitable next step for capitalism. Why? Customers will keep demanding more convenience and more personalization from companies while also demanding lower prices. Companies must reduce their variable costs to make this happen. That means selling products and services customers love — with fewer humans involved. Dystopian? Yes. Inevitable? Yes. Luddites will not be able to suppress humanity's desire for a world that feels purpose-built for each person. As a human, I am compelled to discuss and enable ways for other humans to live their best professional life. For most people, their "best life" will not be spent working the collection of crappy jobs this new wave of automation will displace. As an investor, I'm compelled to 1) bet on the natural behavior of humans to prioritize convenience and individualism above almost everything else; and 2) invest in companies that empower the subset of individuals with the drive to keep themselves unconformable to reach their potential. Automation is key to serving both at scale. Combined, audience and automation are magic ingredients. And these two attributes are core to my investment strategy at CAGR. They allow our portfolio companies to sell leverage to others. That enables more people across the world to move without permission. That's work worth doing. Let's go.